Afghanistan: Qatar and Turkey become Taliban’s lifeline to the outside world

The Taliban’s celebratory gunfire crackled over Kabul as the West pulled out this week. But militancy alone is likely to leave the Taliban on its own – globally isolated, with millions of Afghans facing an even more uncertain future.

The world’s powers are now scrambling to exert influence amid the return of the country’s Islamist rulers. And in the process two nations from the Arab and Muslim world have been emerging as key mediators and facilitators – Qatar and Turkey.

Both are capitalising on a recent history of access to the Taliban. Both eye opportunities. But both are taking a gamble too – which could even stoke old rivalries further afield, in the Middle East.

Officials in the small, gas-rich state of Qatar in the Gulf have provided the lifeline for countries trying to exit.

“No-one has been able to do any major evacuation process out of Afghanistan without having a Qatari involved in some way or another,” explains Dina Esfandiary, a senior adviser at the International Crisis Group, a think tank which studies global conflict.

“Afghanistan and the Taliban will be a significant victory for [Qatar], not just because it will show that they’re able to mediate with the Taliban, but it makes them a serious player for the Western countries that are involved,” she told the BBC.

As Western countries fled Kabul, the diplomatic value of these contacts surged. The Twitter feed of Qatar’s Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, Lolwah Alkhater, reads like a conveyer belt of retweeted tributes from world powers.

“Qatar… continues to be a trusted mediator in this conflict,” she wrote earlier this month.

But bridging a trail to the Taliban may still contain risks for the future, including the capacity to aggravate one of the Middle East’s fault lines. Turkey and Qatar are closer to the region’s Islamist movements, which frequently creates tension with powers like Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who see such groups as an existential threat.

If the two states are strengthened by doing the world’s diplomacy with the Taliban in South Asia, could the ripples travel to the Middle East?

Dina Esfandiary says the Taliban’s surge back to power constitutes a renewed swing towards Islamism – a political ideology that seeks to reorder government and society in accordance with Islamic law – but she says for now it remains contained to South Asia.

“It is for Afghanistan, it doesn’t mean it’s the case for the [Middle East]. Over the course of the last 10 years the region has gone back and forth non-stop between Islamist groups and non-Islamist groups,” she says.

Talking to the Taliban

During the Taliban’s original spell in power in the 1990s only three countries had formal ties with them: Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

The latter two cut all remaining official relations after the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US. However, covert funding from Saudi individuals reportedly went on for years afterwards. Saudi officials have previously denied the existence of any formal funding to the Taliban and said there are stringent measures to stop private cashflows.

But as the presence of US troops in Afghanistan became more unpopular among Americans, the door opened to states who could do the diplomacy.

For Qatar and Turkey, contact with the Taliban developed in different ways.

As President Barack Obama’s administration sought to end the war, Qatar hosted Taliban leaders to discuss peace efforts from 2011.

It has been a controversial and chequered process. The sight of a Taliban flag fluttering in the glittery Doha suburbs offended many (they shortened the flagpole after an American request). For the Qataris it helped develop a three-decades-long ambition for an autonomous foreign policy – which it sees as crucial for a nation that sits between the regional poles of Iran and Saudi Arabia.

The Doha talks culminated in last year’s deal under President Donald Trump for an American pull-out of Afghanistan by May this year. After taking office, Joe Biden announced that he was extending the deadline for a full withdrawal until 11 September.

‘Cautious optimism’

Turkey, which has strong historical and ethnic ties in Afghanistan, has been on the ground with non-combat troops as the only Muslim-majority member of the Nato alliance there.

According to analysts, it has developed close intelligence ties with some Taliban-linked militia. Turkey is also an ally of neighbouring Pakistan, from whose religious seminaries the Taliban first emerged.

Last week, Turkish officials held talks with the Taliban lasting over three hours, as chaos gripped Kabul airport. Some of the discussions were about the future operation of the airport itself, which Turkish troops have guarded for six years. The Taliban had already insisted Turkey’s military leave along with all other foreign forces to end Afghanistan’s “occupation”. But last week’s meeting appeared to be part of a broader agenda, analysts say.

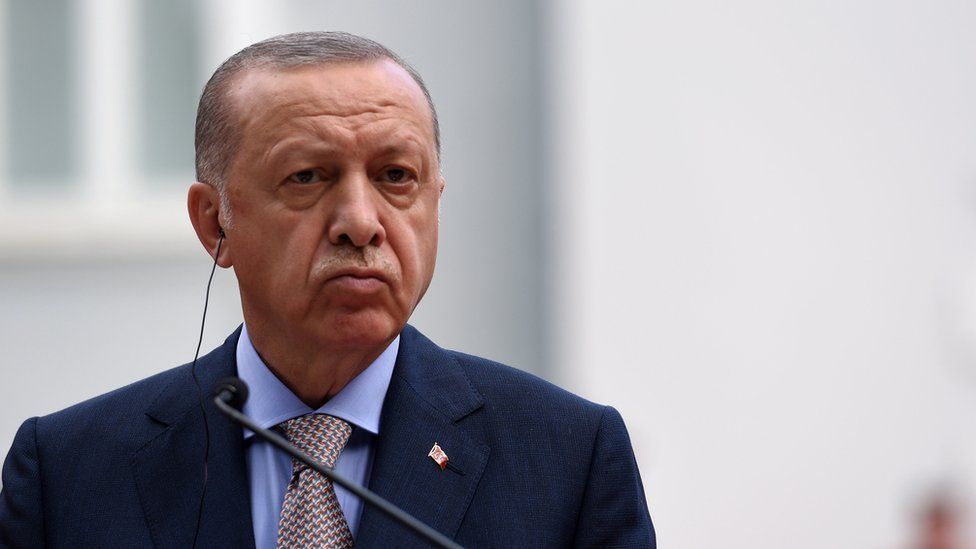

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said he viewed messages from Taliban leaders with “cautious optimism”. He added that he would “not get permission from anyone” about who to talk to, when asked about criticism over contact with the group.

“This is diplomacy,” he said during a press conference.

He added: “Turkey is ready to lend all kinds of support for Afghanistan’s unity but will follow a very cautious path.”

Prof Ahmet Kasim Han, an expert on Afghan relations at Istanbul’s Altinbas University, believes dealing with the Taliban provides President Erdogan with an opportunity.

“To make their grip on power sustainable, the Taliban need international aid and investment to go on. The Taliban are not even able to pay for the salaries of their government employees today,” he told the BBC.

He says Turkey may try to position itself as “guarantor, mediator, facilitator” – as a more trusted intermediary than Russia or China – who have kept their embassies open in Kabul.

“Turkey can serve that role,” he says.

Reputational risk

Many countries have attempted to maintain some form of contact with the Taliban since its take-over of Kabul, particularly through the Doha channel. But Turkey is among those in a stronger position to develop ties on the ground; albeit a situation that is full of risk.

Prof Han also believes further ties in Afghanistan allow President Erdogan to “broaden the chessboard” of his foreign policy and play to his AK Party’s support base.

“They consider Turkey as a country with a manifest destiny – an exceptional position within the Muslim world. It is based on Turkey’s past and its Ottoman heritage as the seat of the caliphate.”

“However, if that role amounts to a point where any country including Turkey becomes the sponsor… establishing a Sharia regime which is brutal in its practices… Turkey should not want itself there,” he adds.

Mr Erdogan’s move reportedly has more “rational” motives too – by improving Turkey’s strained relations with the US and Nato, and building influence to prevent flows of Afghan refugees to Turkey.

As for Qatar, officials will hope its role as a mediator will diminish, rather than aggravate, years of turbulence in the Gulf.

Doha has brokered negotiations between competing factions in several of the Middle East’s major conflicts. But in the wake of Arab Spring, its Gulf rivals accused it of siding with Islamists. In 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain cut ties – since restored – accusing Qatar of getting too close to Iran and fuelling instability via its state-owned news channel Al Jazeera; claims it rejected.

For now, with a deeply uncertain situation for the people of Afghanistan, Qatar and Turkey are among those talking to the Taliban for many in the outside world; while China and Russia also compete for future access in Kabul.

Prof Han says this amounts to a least worst option, what he calls the most “collaborative approach”.

“Turkey, being a member of the West, is more susceptible to pressure from the West over [human rights] issues,” he says.

The ripples from the Taliban’s take-over have only just begun. The lives of millions of ordinary Afghans depend on how they spread out.